119 addison rd 'ferndale'

da/2020/0729

da201800562

ca201600025

da201500616

Marrickville's oldest house?

Peering in at Ferndale through the cyclone fencing on Addison Road is an odd experience. The house looks forlorn, covered in graffiti with a long concrete path traversing a barren lawn, terminating at a set of concrete steps. Mounting the short flight onto a concrete verandah, covered by what looks like a miniature carport you come face to face with a house and a charmless countenance. The lack of eaves on the front of the house suggest a covered verandah has fallen off at some stage, perhaps at the time the timber cladding was replaced. The window shutters, barely discernible under the spray paint hint at a former life as a farmhouse. The house does not entice you with expectation, merely nervous curiosity. It is a sad house.

Its interior proclaims a house that makes no pretence of ever having been a home. It is full of things that tell a story of dysfunction. Mattresses stacked against walls, pallets that have formed a bed base, bottles filled with urine. The owner has proudly declared this house uninhabitable, worthy only of demolition. But among the squalor, some gems remain. The fireplace is intact and there is a beautiful double arched sash window on the western wall. As you enter Ferndale, the tongue and groove internal panelling, now so coveted, is in place. Hints of a former beauty begin to reveal themselves.

A fourth development application has been submitted for this property and the neighbours are weary of fighting against proposals for an overwhelming, oversized dwelling that will dominate the surrounding landscape. Some continue the fight. Others have moved away. But as the battle wages, some remarkable information about Ferndale has emerged. Claims have been made that the house dates to 1860. Others say that the house is newer than that but the chimney is mid-19th century. If these claims are correct, this house or at least the chimney pre-dates Marrickville and is far too important to be bulldozed.

I began the search for its story.

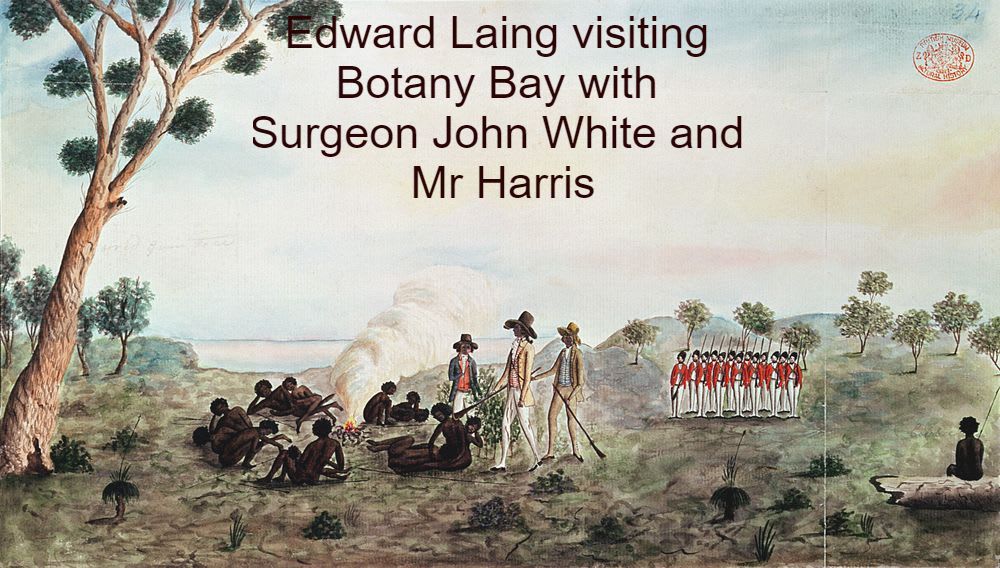

Much of Marrickville sits on land grants made to Thomas Moore in 1799 and 1803. He and other early grantees sold their holdings to Robert Wardell who acquired about 2,000 acres in the area and as such, the stories of many Marrickville homes feature that gentleman in their provenance. Ferndale is different, it sits on an earlier grant made to Edward Laing in 1794 and was named Laing’s Hill by Lieutenant Governor Francis Grose. The original land grant is in the Mitchell Library and tells the story of Laing’s Hill from its inception. It is a surreal experience to be holding and reading a document that has been signed by so many of Australia’s colonial royalty, men whose lives fill our history books and whose marks rest on a piece of parchment that is 225 years old.

Its interior proclaims a house that makes no pretence of ever having been a home. It is full of things that tell a story of dysfunction. Mattresses stacked against walls, pallets that have formed a bed base, bottles filled with urine. The owner has proudly declared this house uninhabitable, worthy only of demolition. But among the squalor, some gems remain. The fireplace is intact and there is a beautiful double arched sash window on the western wall. As you enter Ferndale, the tongue and groove internal panelling, now so coveted, is in place. Hints of a former beauty begin to reveal themselves.

A fourth development application has been submitted for this property and the neighbours are weary of fighting against proposals for an overwhelming, oversized dwelling that will dominate the surrounding landscape. Some continue the fight. Others have moved away. But as the battle wages, some remarkable information about Ferndale has emerged. Claims have been made that the house dates to 1860. Others say that the house is newer than that but the chimney is mid-19th century. If these claims are correct, this house or at least the chimney pre-dates Marrickville and is far too important to be bulldozed.

I began the search for its story.

Much of Marrickville sits on land grants made to Thomas Moore in 1799 and 1803. He and other early grantees sold their holdings to Robert Wardell who acquired about 2,000 acres in the area and as such, the stories of many Marrickville homes feature that gentleman in their provenance. Ferndale is different, it sits on an earlier grant made to Edward Laing in 1794 and was named Laing’s Hill by Lieutenant Governor Francis Grose. The original land grant is in the Mitchell Library and tells the story of Laing’s Hill from its inception. It is a surreal experience to be holding and reading a document that has been signed by so many of Australia’s colonial royalty, men whose lives fill our history books and whose marks rest on a piece of parchment that is 225 years old.

Francis Grose was the leader of the NSW Corps, the notorious ‘Rum Corps’, who acted as governor when Arthur Phillip returned to England in 1792. In his two years as Lieutenant Governor he overturned Phillip’s administration, established military rule in the colony, abolished civil courts and made land grants to his officers who he provided with convicts to farm the lands. Edward Laing received 100 acres in the area known as Bulanaming in 1794. He was Surgeon’s Mate to the NSW Corps who had come to the colony in 1791 aboard The Pitt. He erected a tent on the north side of his grant. His friend and colleague Thomas Rowley who he had met aboard the Pitt, was given the adjacent grant and called his ‘Kingston’. Their tents were within shouting distance of each other and they built a track that separated the two parcels of land. That track is now called Stanmore Road.

Edward sold his grant to Thomas Fyshe Palmer only five months after he received it and returned to Sydney. Thomas’ story was an eye opener to one who believed that convicts spent their sentence at best in servitude and at worst in irons on a daily diet of hard labour. Thomas was a minister of the Unitarian Church and deemed a political prisoner. He had been convicted of insurrection at a time when the English were nervously watching a revolution unfold across the channel in France. He was sentenced to seven years transportation but arrived with his companion James Ellis who had emigrated as a free settler, a letter of introduction to the governor of New South Wales and enough cash to be able to purchase Laing’s Hill for £84. Once he arrived, he went into business with James and John Boston and spent his sentence building a business. Laing’s Hill was covered in turpentine which he began to fell to supply the government stores as was required under the conditions of the grant. As the land was gradually cleared it became farmland but was a failure. Thomas sold the land in 1800 to Eber Bunker for £90 and left Australia in a boat he had built in order to return to England. When he landed en route in Guam he was arrested as a heretic and imprisoned. He died there in 1802 with James by his side.

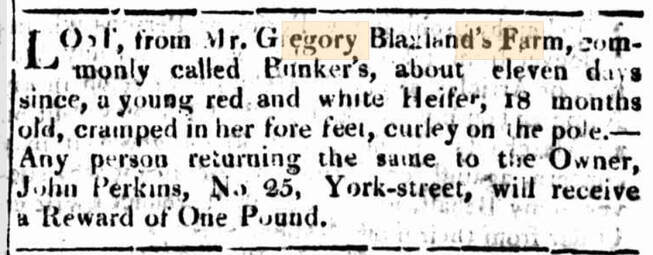

Eber Bunker was born in America of British parents. He was a whaler by occupation who returned to England once the British introduced tariffs to whale products and the Americans were unable to compete. He set sail for New South Wales as part of the Third Fleet, captaining the William and Ann, a former whaling ship that now would transport 188 convicts. He arrived at Sydney Cove in August 1791 where he took up his former career as a whaler. He led the first ever whaling expedition in Australian waters. He roamed the globe for several more years in his capacity as a whaler, but 1799 saw him back in Sydney where he would base himself for two winters of whaling in Australia and New Zealand waters. In March 1800, he bought Laing’s Hill before setting off for the winter whaling season. Over the next few years he lived a boy’s own adventure lifestyle, discovering a group of islands on the Great Barrier Reef, which are named the Bunker Group of Islands and transporting the first settlers to Tasmania in 1803. He received 4,000 acres on Georges River near Liverpool as a reward for his dedication to the colony and he brought his wife and children from England to settle here. Margaret died in March 1808, and in April Eber sold Laing’s Hill and returned to sea. He eventually settled on his property at Liverpool, now enlarged with a subsequent grant of 400 acres and remained there as a wealthy pastoralist.

Laing’s Hill was now in the hands of John and Gregory Blaxland who had paid £105 for it in April 1808. The Blaxland boys were among Australia’s earliest wealthy immigrants. Friends of Sir Joseph Banks, they were promised land, convict servants and free passage. Gregory arrived in 1806, located 4000 acres and was promised 40 convict servants. John arrived the next year.

Eber Bunker was born in America of British parents. He was a whaler by occupation who returned to England once the British introduced tariffs to whale products and the Americans were unable to compete. He set sail for New South Wales as part of the Third Fleet, captaining the William and Ann, a former whaling ship that now would transport 188 convicts. He arrived at Sydney Cove in August 1791 where he took up his former career as a whaler. He led the first ever whaling expedition in Australian waters. He roamed the globe for several more years in his capacity as a whaler, but 1799 saw him back in Sydney where he would base himself for two winters of whaling in Australia and New Zealand waters. In March 1800, he bought Laing’s Hill before setting off for the winter whaling season. Over the next few years he lived a boy’s own adventure lifestyle, discovering a group of islands on the Great Barrier Reef, which are named the Bunker Group of Islands and transporting the first settlers to Tasmania in 1803. He received 4,000 acres on Georges River near Liverpool as a reward for his dedication to the colony and he brought his wife and children from England to settle here. Margaret died in March 1808, and in April Eber sold Laing’s Hill and returned to sea. He eventually settled on his property at Liverpool, now enlarged with a subsequent grant of 400 acres and remained there as a wealthy pastoralist.

Laing’s Hill was now in the hands of John and Gregory Blaxland who had paid £105 for it in April 1808. The Blaxland boys were among Australia’s earliest wealthy immigrants. Friends of Sir Joseph Banks, they were promised land, convict servants and free passage. Gregory arrived in 1806, located 4000 acres and was promised 40 convict servants. John arrived the next year.

They refused to grow grain as instructed and instead turned to livestock. The cleared portion of Laing's Hill became a cattle farm. Their flocks of sheep and cattle expanded beyond their coastal grants, and Gregory joined forces with William Wentworth and William Lawson to traverse the Blue Mountains in search of pastoral lands on the other side of the mountains.

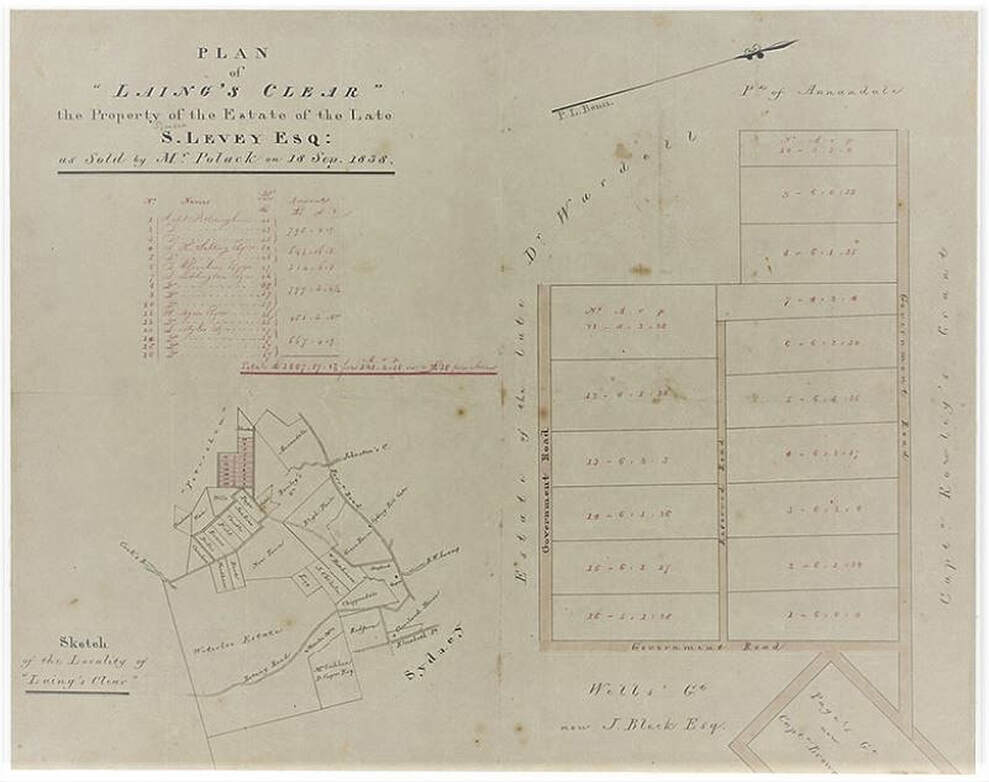

The Blaxlands sold Laing’s Hill to Solomon Levy in 1822. Solomon had been transported to NSW in 1815 after having been convicted as an accessory to theft. He immediately began his career in Sydney in real estate and providing goods to the government. He was pardoned in 1819. By 1825 he was turning over £60,000 per year and by 1828, in partnership with Daniel Cooper, they owned most of the land that is now Waterloo, Alexandria, Redfern, Randwick and Neutral Bay.

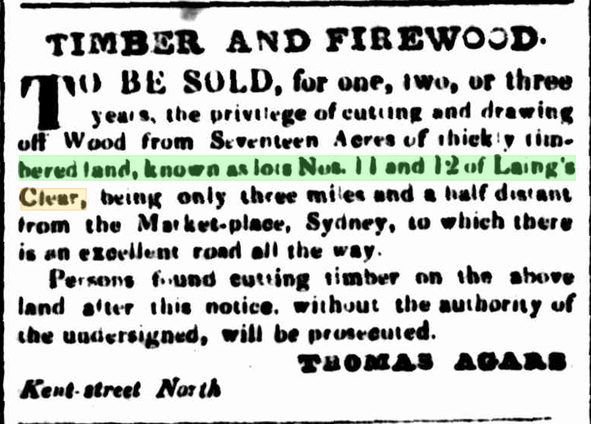

When Solomon died in 1833 his vast land holdings were sold, and Laing’s Hill was described as forest land in his will. It was subdivided and sold in 1838. Lots 11 and 12 of Laing’s Hill were bought by Thomas Agars in 1838 who had an import store in Kent Street and exported beef to London. He became an alderman on the City of Sydney Council and the Agar Steps running from Kent Street to Upper Fort Street still bear his name.

When Solomon died in 1833 his vast land holdings were sold, and Laing’s Hill was described as forest land in his will. It was subdivided and sold in 1838. Lots 11 and 12 of Laing’s Hill were bought by Thomas Agars in 1838 who had an import store in Kent Street and exported beef to London. He became an alderman on the City of Sydney Council and the Agar Steps running from Kent Street to Upper Fort Street still bear his name.

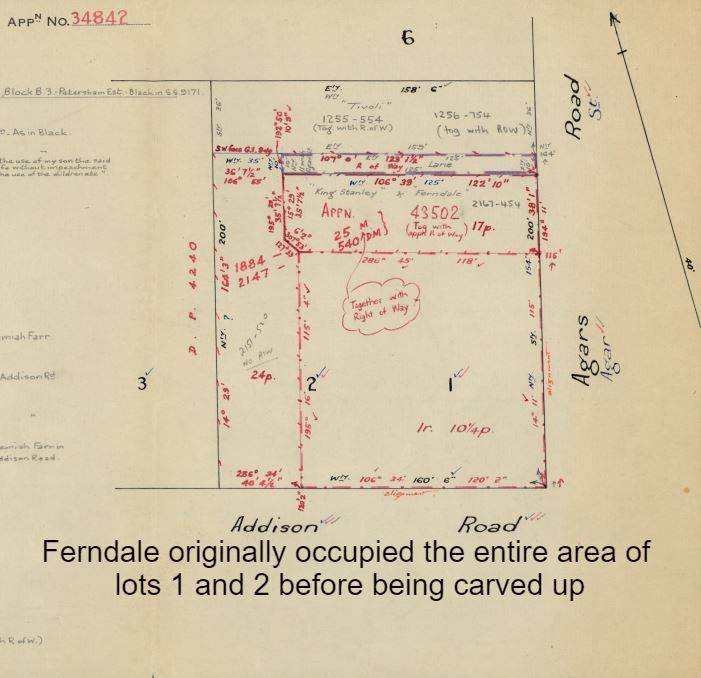

The purchase of his lots took several years to settle as his land abutted the estate of the by now deceased Robert Wardell who had moved his fence line and cleared the additional land, the encroachment of which had reduced Thomas Agars purchase from 17 acres to 14. Thomas refused to settle the purchase until the title reflected the actual land measurement, especially as the cleared land was of higher value and a corresponding deduction to the purchase price had been made. Thomas’ land extended along Addison Road from England Avenue to Wemyss Street and north to Emily Street (we now call it Newington Road). Thomas advertised a licence to fell timber and remained in Sydney while the land was cleared. He never lived in the area.

After Thomas died in 1852 the land was subdivided and eventually sold in 1874 as the Agars Estate. The portion that Ferndale stands on was described as lot 2. There is no evidence that a house was standing on the estate when it was sold, which is not to say there was none. An extensive search of the Richardson and Wrench collection (who sold Agars Estate) at the Mitchell Library could not unearth the subdivision plan, which may have identified any buildings on the estate.

Lot 2 of Agars Estate was bought by John Long of Botany, who had bought lot 1 as well. He flipped the land three months later to Edward Rofe, a boot manufacturer. Edward then bought lots 3, 4 and 5 as well, so had a substantial stretch along Addison Road. Edward lived in a timber house with vegetable gardens, a paddock and the last vestiges of a turpentine forest next door to where Ferndale would eventually be built.

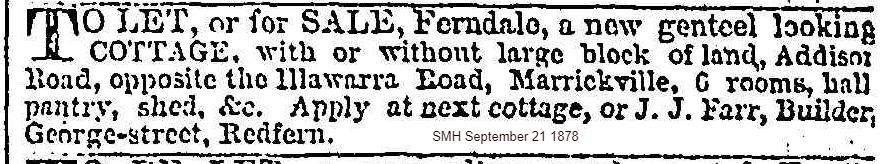

He sold lots 1 and 2 in 1878 to Joshua Jeremiah Farr. Joshua was a carpenter who had worked at the Tooths Brewery on Broadway when he first arrived in Australia in 1855. He shortly after began working as a builder in the Redfern area and was joined by his brother James in the business.

Lot 2 of Agars Estate was bought by John Long of Botany, who had bought lot 1 as well. He flipped the land three months later to Edward Rofe, a boot manufacturer. Edward then bought lots 3, 4 and 5 as well, so had a substantial stretch along Addison Road. Edward lived in a timber house with vegetable gardens, a paddock and the last vestiges of a turpentine forest next door to where Ferndale would eventually be built.

He sold lots 1 and 2 in 1878 to Joshua Jeremiah Farr. Joshua was a carpenter who had worked at the Tooths Brewery on Broadway when he first arrived in Australia in 1855. He shortly after began working as a builder in the Redfern area and was joined by his brother James in the business.

Joshua built Ferndale in 1878, and it was the first recorded house he built in Marrickville.

For 16 years Joshua was an alderman on Redfern Council until he relocated to Marrickville in 1882. He then joined the Marrickville Council where he sat as alderman for more than 20 years, and mayor for one. Joshua was heavily involved in the local community especially his beloved St Clements Church. He settled into Addison Road with his family, a stone’s throw from Ferndale in a house called Cheltendale. It’s still there at 113 Addison Road. By 1894 Joshua had built a larger house next door to Cheltendale called Corra Lynn and lived there until his death in 1902. Corra Lynn was on the site now occupied by the Glow Worm Bicycle Shop. Three of his children lived around the corner in Agar Street.

Ferndale’s first occupants were George and Sarah Butterfield who had married at Newtown in 1876. Variously described as an engineer or draughtsman, George assembled Australia’s first planisphere which was displayed at the 1870 Intercolonial Exhibition and then went into mass production. He lived in Ferndale for about two years before moving around the corner to 14 Wemyss Street.

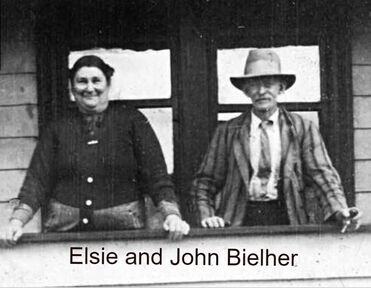

Ferndale saw a succession of tenants with none staying more than a couple of years. During the 1940s the rear of the property was used as a caryard. It remained in the Farr family until 1950 when it was advertised as a development site and was bought by John and Elsie Biehler who were farmers from Ryde. They made Ferndale their home, its first permanent family, but John died in 1959 and Elsie in 1960.

The march through time continued with Ferndale seeing little but neglect and threat of demolition until it has got to the state that it’s in now. Its challenge is to beguile someone with copious amounts of determination and indomitability to bring back its 19th century charm.

The march through time continued with Ferndale seeing little but neglect and threat of demolition until it has got to the state that it’s in now. Its challenge is to beguile someone with copious amounts of determination and indomitability to bring back its 19th century charm.

And so to the myths that have grown around the house.

Ferndale was built around 1860 at the time Marrickville was proclaimed a municipality.

Wrong. It was built in 1878.

The chimney is internal, not bolted onto the outside of the house and therefore must have been standing when Joshua built around it.

Unlikely. There are many photos of 19th century timber houses with internal chimneys. The chimney is made of sandstock bricks which were commonly used in the 1870s and 1880s as Marrickville grew. My own previous house has one, and it was built in 1886. There is currently no evidence that a house stood on the site until Joshua Farr built Ferndale.

Ferndale was built around 1860 at the time Marrickville was proclaimed a municipality.

Wrong. It was built in 1878.

The chimney is internal, not bolted onto the outside of the house and therefore must have been standing when Joshua built around it.

Unlikely. There are many photos of 19th century timber houses with internal chimneys. The chimney is made of sandstock bricks which were commonly used in the 1870s and 1880s as Marrickville grew. My own previous house has one, and it was built in 1886. There is currently no evidence that a house stood on the site until Joshua Farr built Ferndale.

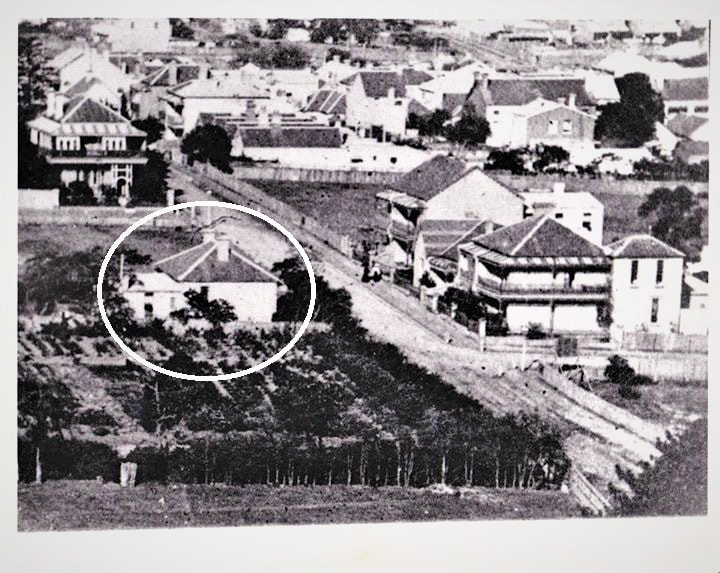

- This photo is of Ferndale, surrounded by orchards.

Ferndale is remarkable in that it is a timber cottage still standing after more than 150 years. I wonder how many brick houses built today will still be here after a century and a half.

Ferndale is not Marrickville’s oldest house, but in a competition for Marrickville’s saddest house, it’s a real contender.

Copyright © 2020 Marrickville Unearthed. All rights reserved